Context

Today’s world showcases unprecedented levels of technical and technological development. It affords scores of lifestyle options permitting many to pursue their dreams. Thing is, there is no barrier insulating an individual from experiencing some form of injustice no matter how fortunate their circumstance.

It gets worse. Your average person typicaly demonstrates a fair amount of haste to seek redress for wrongs (perceived or real) when social issues are in the balance. Where matters of environmental equity are on the line though, such alacrity may not be forthcoming. This penchant for inaction holds true whether or not your affecteds live in Developed, Developing, Least Developed or in small island states such as ours.

Nature/or nature’s services is a common denominator (of loss) in instances where environmental infringement occurs. This brings/carries impact beyond the individual - to groups. When something like that happens the term ’environmental injustice’ comes to bear.

Access to justice in such a context is never clear-cut, always expensive and more often than not, spans long periods of time. To make matters worse, some countries do not recognise environmental law, placing environmental accountability overall in a fairly fluid space. This is now becoming evident in Tobago the more rural, smaller partner in the twin-island Republic of Trinidad and Tobago.

## Loading required package: ggplot2

## ℹ Google's Terms of Service: <https://mapsplatform.google.com>

## Stadia Maps' Terms of Service: <https://stadiamaps.com/terms-of-service/>

## OpenStreetMap's Tile Usage Policy: <https://operations.osmfoundation.org/policies/tiles/>

## ℹ Please cite ggmap if you use it! Use `citation("ggmap")` for details.

## ℹ <https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/staticmap?center=11.13372,-60.788606&zoom=13&size=640x640&scale=2&maptype=terrain&language=en-EN&key=xxx-Nfd_JMd-U>

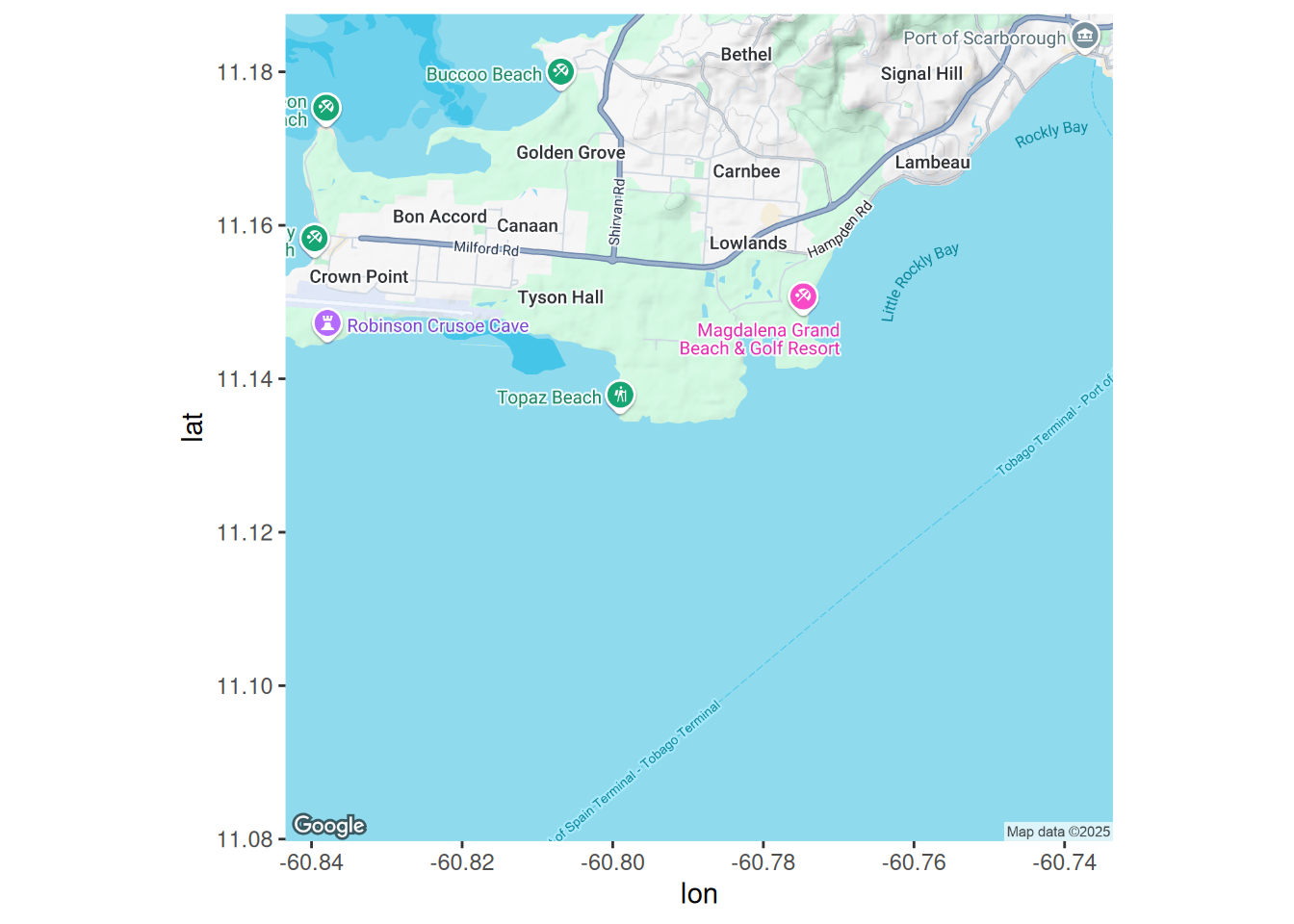

Figure 1: Map of coastal zone affected by the spill

But at the end of the three month mopping up exercise, visible damage to the coastal environment had incurred. Concern was also rising regarding public health, well-being and damage to the local economy. The outlook for justice in context is not looking good.

The Tobago economy is pinned to nature-based tourism as there is little recourse to conventional income streams such as manufacturing or even mining for oil and gas. Its remote nature cements the economic direction, as competitive industrial activity is limited by Tobago’s size and relatively infrastructure.

Adding to the bleakness, Government’s chances of finding and binding the parties responsible for the spill seem minimal - allowing if so, the culprit or culprits will have means to make reparations.

There could be good news; a claim is being entertained by the managers of the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds mechanism. The IOPC promise in the eyes of the Tobago people is a positive gesture from the international oil producing community - which pays into the fund. Still there is also a growing feeling it may be vastly inadequate. That there will not be money enough to cover the cost of mop-up, which is almost complete. Neither will it be enough to fund restoration works along shoreline and nearshore sub-sea areas - critical to the area’s biodiversity and therefore to Tobago’s food security.

There is also mounting concern that no formal conversations are being entertained about reparation for fisherfolk, displaced households, property owners in the hospitality sector or even toward soothing the discomfort of the general population.

The matter of ‘settling’ the wrongs done to Tobago’s natural environment (and therefore its people) bear the markings of a landmark case in maritime law at the very least. How the situation plays out will no doubt interest small nations (and big business) the world over - As it pits the endowed against the unwitting, puts profiteers from big oil against an island population wanting redress for damage to their natural environment and to way of life.

The village

Lambeau lies along Milford Road, once the main artery between Tobago’s southernmost point and capital Scarborough. The construction of the Claude Noel Highway in 1987 orphaned this community, side-lining traffic and consequently pace of development. Nevertheless the villagers adjusted to the price of progress, buying into the Less is More principle.

By 2020 patience began to pay off. Local fishers built up a fresh fish market which complemented a unique and quaint hospitality sector, spanning unsophisticated eateries, simple accommodations and sporting events such as road races and kite sailing.

Village homes, schools, churches and playing fields are set high above the water so as to catch the incoming eastern breezes. The fresh air, unrestricted view of the eastern horizon - where imaginative minds could ‘see’ the west coast of Africa, is favourable to retirees as well as the ailing. Or, those merely aching for that fresh air. People from the wider population value Lambeau’s long undisturbed swathes of pink sand for beach-combing, walking, shore-based fishing and all the others things a friendly beach provides.

Just immediately south of the beach is Lowlands Estate. Once a colonial sugarcane plantation, today this acreage sports an alluring array of villas, condominiums, a 200 room hotel along with a 36 hole golf course. On the seaward side, the estate is bordered by an exposed shoreline which, while seemingly hostile, speaks to a rich and diverse seafloor mere meters away. And indeed, the relatively shallow reefs of Petit Trou have long been exploited by fishermen and sport divers alike.

Continuing southward along the Lowlands coast, the mangrove stands of the Petit Trou Lagoon replace the windswept vista of sea-grape, sea almond, cactus, mahoe and coconut palm. The shallow lagoon is host to a variety of bird and fish species, life encouraged to great extent by the surrounding mangrove forest to feast, roost and spawn.

Intriguingly the Petit Trou Lagoon was not always surrounded by mangrove. The fringe there now is the inadvertent result of a decision made over 70 years ago by then Scarborough town planners - to route municipal run-off from the Lowlands collective into the lagoon. That simple expedient exercise, normal for the times, created the sweet-saltwater mix that aided the propagation and proliferation of red and white mangrove.

Yet the spill event of February 2024 diminishes the value of yesteryear’s intervention. Lambeau villagers are coming to realise the area’s resilience to stress is compromised. Crude oil from the spill found its way into the Petit Trou lagoon, depositing thick black goo over the mangrove root systems already suffering from sargassum influx. The sticky mess also covered the length of shoreline all the way to Scarborough just north.

February to May

“The National Oil Spill Contingency Plan (NOSCP) is designed to mitigate the impact of all oil spills on the environment. It establishes time frames for oil spill response and increasing collaboration among partner agencies”. [NOSCP 2013]

At 7.00 am on February 7th the Trinidad and Tobago coast guard triggered the response mechanism. The news of the capsized barge was startling enough for SCUBA shop operator Alvin Douglas to “cancel my biggest sport diving group for the year” to go and assist the Tobago Emergency Management Agency (TEMA). The All Tobago Fisherfolk Association (ATFA) also sent a team which arrived by pirogue. It did not take those present long to realise that dealing with an overturned vessel leaking ‘petrochemical’ was a job well beyond their capacity.

Not that it stopped anyone. Local divers took to the water, braving the oily waters to get a handle on the situation. Alvin Douglas went first, disregarding the fear of contamination from - anything really, as nothing about anything was yet known. Not the vessel’s name, not its originating or even home port, and certainly not the nature of the contents in the hull.

Thirty-six hours later the situation had not improved. Had worsened in fact, as the overturned hull rocked in the choppy water and began releasing ‘oil-like substance in earnest. In the meantime information coming in from citizen reporters provided a composite but still unclear picture. Calls relayed from fishermen plying their trade off the north coast off Trinidad recalled sightings of a barge that had been listing, leaving a trail ‘oil’ substance as it headed east on a heading between Grenada and Tobago.

By day 4 the general consensus among the marine fraterity was that a barge carrying a petrochemical class of cargo had departed a Venezuelan port a week earlier that matched the description of the MV Gulfstream (the name supplied by the indomitable Alvin Douglas). It was also fast entering the minds of the House of Assembly - the local arm of government with responsibility for Tobago that the Lambeau situation was a but a glimpse into an unwelcome future.

The island by virtue of geography was lying downstream of the Galeota Block, a nationally owned oilfield that is under reassessment for further expansion. Further south along the south continent are the huge Guyanese finds which also under rapid expansion. Also adding to the grim scenario is the Suriname offshore play, just south of Guyana’s waters.

The first 15 days of the mop up attracted much public interest but as the cleanup team got to grips with the leak, focus turned to the events that might have led to the barge coming to ground in Tobago. Satellite tracking systems place the craft by now tentatively identified as ‘Gulf Stream’, in proximity to Venezuelan crude (oil). Social media later provided video the Gulfstream suffered structural failure while at sea. Speculation suggested those problems escalated, causing the tow vessel to cut the towline, after which it ran aground in the vicinity of Lambeau.

Further investigations revealed the towing vessel, allegedly a tug called Solo Creed was flying a flag of convenience. At time of writing Solo Creed has not regenerated an Automatic Information Systems (AIS) signature, leaving the maritime world blind to its whereabouts. The situation therefore, five months after the oil spill lends to several possible futures.

Allowing the Trinidad and Tobago government will get help from the International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage and enough is acquired to pay the huge stack of bills due to the cleanup effort, the village of Lambeau will just have to make do with whatever money is left to attend to compensation and restoration. Which may fall far short, since compensation for compromised nature is not defined in local law.

The outlook

Trinidad and Tobago is no newbie to boom-driven or windfall development. T&T entered the commercial oil industry in 1908, riding the highs and the lows of the sector. But the wealth that came with oil and gas also brought the ‘resource curse’, a phenomenon economists often allude to when speaking on (importance of) economic diversification.

As it turned out Trinidad and Tobago, instead of being able to wean itself off a fossil fuel driven economy, finds itself today in the un-enviable position of having to continue oil and gas extraction in a world that is thinking Renewables.

Unfortunately for Tobago, divorced as it is from the bigger island by geography, economy there is powered mainly by government spending and after that, tourism. This places Bellaforma (name given to it by Christopher Comumbus) between the proverbial rock and hard place.

The Tobago hospitality industry was just coming into its own when the Gulf Stream spill occurred. And with Trinidad refocusing on drilling in order to capitalise on the world’s increasing appetite for oil, the smaller island is fearful there could be more spills from illegal and irresponsible oil transport.

These worries are not allayed by the fact that the ill-fated Gulfstream was being towed from oil rich, cash poor nearest neighbour, Venezuela. In short, human generated risks, plus threats posed by nature, such as more frequent and stronger hurricanes, will compromise Tobago’s ability to adjust to the shifting climate. Unless the IOPC money comes through in a timely fashion - And is enough to restore the Lambeau community, its beaches, reefs and the Petit Trou lagoon into some semblance of normalcy - where it was before the barge came to ground.

The optimistic view held by the local community is money from the IOPC will flow and all will be well. The (more) likely scenario suggests however, compensation will go primarily to the away support team which implemented the clean-up effort.

Second, but also a matter of priority, some will go to local contractors for services that supported the ground effort, such as shoreline mop up and removing and retrieving the crude for refining. Moreso the convoluted nature of procurement for contracted services may well find the Tobago House of Assembly billing the State for deploying its cadre of daily paid workers citing that expense as priority.

Third - money to appease the affected Tobago community. These may be fishers forced off their grounds, home-owners told to vacate during the clean-up. Odds are compensation going to those ‘affected’ will not greatly improve their lot.

Government past practice suggests money will not be going directly to the Tobago House of Assembly for restoration of shoreline, sub-sea environment or even the lagoon with its mangroves - As the body competent is the Institute of Marine Affairs, the Trinidad based central government entity with a track record, appetite and lately, capacity for accessing ‘outside’ funds.

Also and importantly in the timeline the IMA at time of writing has not quantified or substantiate the impact or possible ecological future of the locale affected by the spill. They are hedging, as is to be expected on the side of caution. As such that work is still ongoing.

However to the Lambeau people, to the natural space of the area and to the creatures who inhabit that space, time is of the essence for any help that is forthcoming. Tobago at the time of the spill was slowly clawing its way back from the effects of the 2020-2021 Coronavirus lockdown.

Indeed the Tourism Division of the House of Assembly had been actively wooing airlift both internationally and within the region. Immediately, as news of spill spread, the fruits of those efforts - according to the THA, were eventually harvested by neighbouring holiday destinations Grenada and St. Lucia.

Nobody wants to go to a place smothered by ‘oil-like substance’, as the mainstream media referred to the spill during the first 30 days of cleanup. The upshot is the situation comes down to a case of environmental injustice. One ironically wrought upon a community within an oil producing nation from a spill engineered by a third party - from another jurisdiction.

The Tobago situation bears similarity to the disenfranchisement of the so-called ‘fenceline’ folk - who typically are ’left behind’ in places where natural resources are extracted. Paradoxically, if any good is to come out of the Tobago spill situation, it is that government may rethink their historic reticence to embrace multilateral environmental accords that can better align the country to the SDG 2030 agenda - beyond what suits Trinidad and Tobago decision-makers in the near term.

It could not have been pleasant for the ministerial team, cap in hand at the office of the IOPC, to admit that while Trinidad and Tobago did sign onto the International Convention Relating to Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage 1992 and the Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage 1992, it was not subsequently incorporated into local law.

It is the wider picture however that shows the true environmental travesty that is in the making, made apparent by this Tobago spill. International shipping provides the largest conduit for the transport of oil and gas (and other toxic substances) yet it is one of the least regulated sectors on the planet.

Consider this. The tug Solo Creed was towing the barge Gulfstream while flying a flag of convenience. Government and internationally linked investigations five months on, are yet to locate a culpable party. The implications of convenience flags are not well known by most but its a mechanism well and truly appreciated by those who want to circumvent tax, duck safety stipulations and avoid fair wage bills. Back to the big picture.

Lambeau lies in the vicinity of major oil fields owned by four separate countries. All are entangled in production sharing contracts with numerous private entities. Who in turn, move product using ships that may or may not always be in the fairest of condition. Or, might not be crewed by competent or happy seafarers. There are also several serious conflicts occurring in various political theaters. All require oil and gas. This is a made to order recipe for unscrupulous entrepreneurial activity in the marine space. Justice is a difficult narrative to maintain in such an environment. Environmental justice even more so.

The hoped for outcome

There is a school of thought that justice is based on social contract. Which in turn imposes conditions whereby the few relinquish bits of freedom - or modify some aspect of behaviour to assure the well-being of many. This works well in communities where democracy is practiced. But it is not perfect in the sense that in a court of law, assets are brought into play to offset damages awarded punitively - that is to punish guilty parties after compensation to the plaintiff is done with. Thing is in environmental law, itself a relatively new field, the value of nature is not yet standard. Nor is it bench-marked.

The logical approach under contemporary discussion to imbue values onto natural space and nature’s services, since most business activity requires critical input of one or even both. Yet ecosystems-based accounting, an embryonic discipline in the emerging narrative, is not gaining traction within the conventional accountng framework (where balance sheets live) to a degree it could positively impact identification or resolution of environmental injustices.

In the absence of any broadening of scope - from social to eco-social contract, how then can Lambeau make a claim for compensation and beyond that, seek punitive award? And if it could make the necessary calculations, who would be the select defendant given the loopholes in marine legislation? Getting it all together presents Trinidad, Tobago and Lambeau village with a bellwether moment. The world watches.